Akhenaten: Artistic Development in the Amarna Period

Amenhotep IV, widely recognized as the notorious Akhenaten, was the enigmatic “heretic” pharaoh who ruled during the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Maya M. Tola 20 July 2023

Hatshepsut (c. 1507-1458 B.C.E.) was the fifth pharaoh of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty and arguably the most important among ancient Egypt’s many female rulers. Her 20-year-long reign was an era of peace and prosperity. The kingdom thrived under a flourishing economy, a lucrative trade network, and successful military campaigns. Hatshepsut’s reign was also a peak period for artistic pursuits, and her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri stands out as a fine example of Egypt’s awe-inspiring architectural heritage. Many pharaohs that came after her have claimed the temple as their own.

Hatshepsut was the daughter of Thutmose I, a successful pharaoh, and was married to her half-brother Thutmose II. After Thutmose II died, Hatshepsut was appointed as a regent for her stepson and nephew, Thutmose III. In the seventh year of regency, she made an unprecedented move for power and declared herself to be the ruler, calling herself “King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkara and the Daughter of Re.”

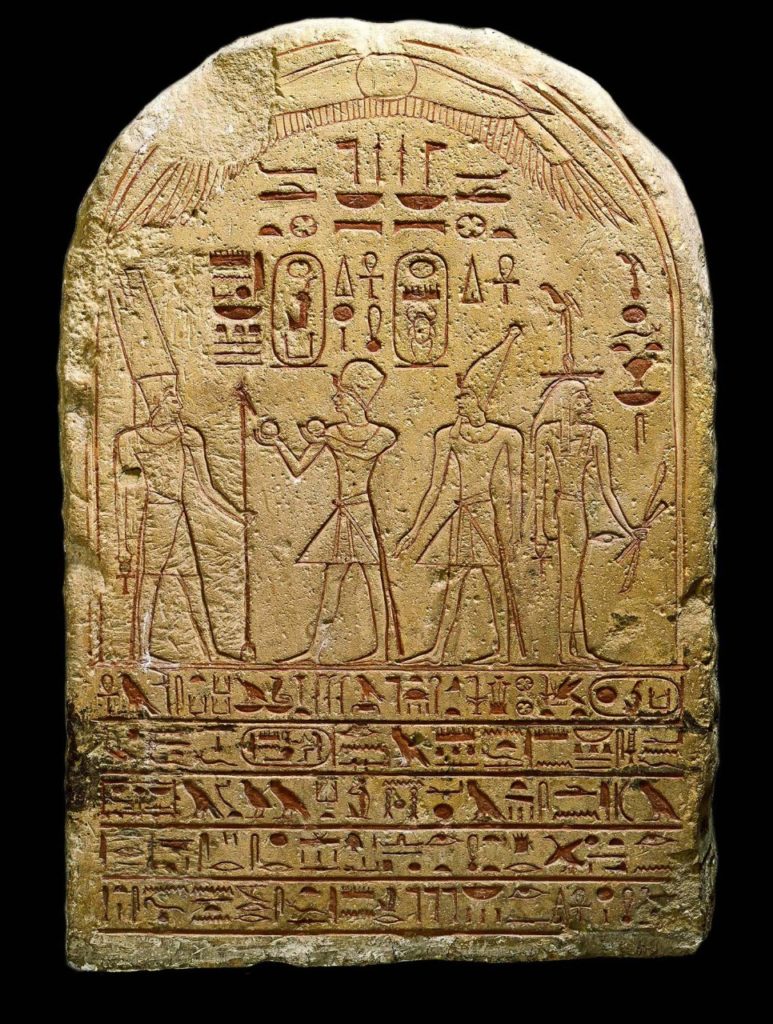

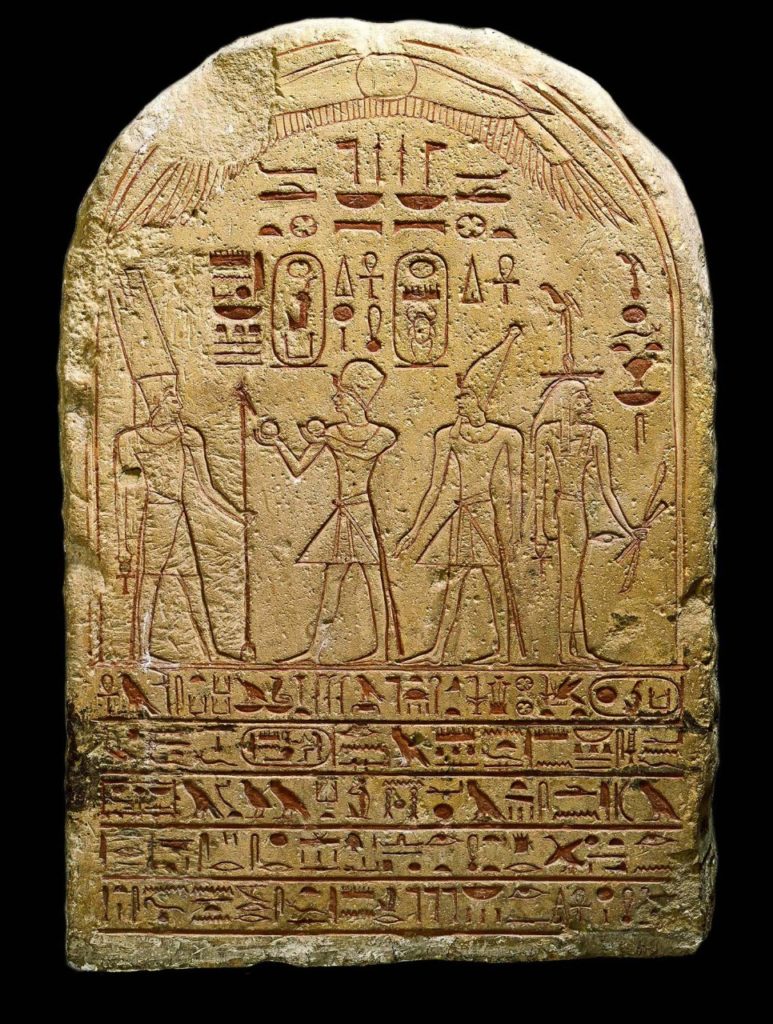

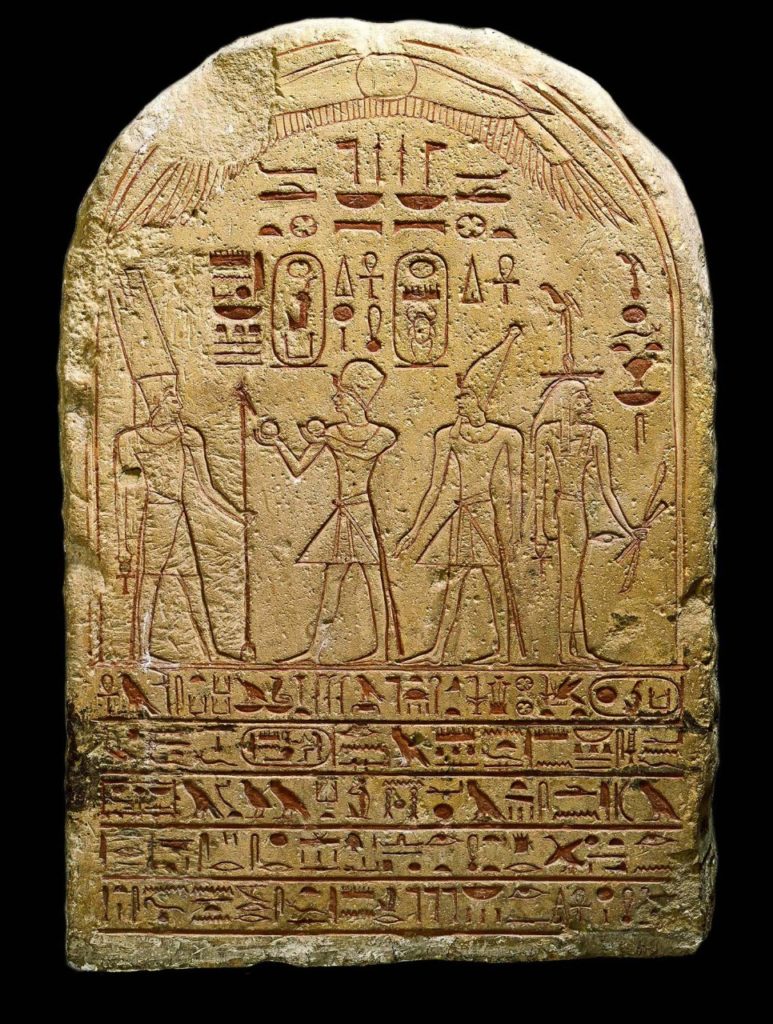

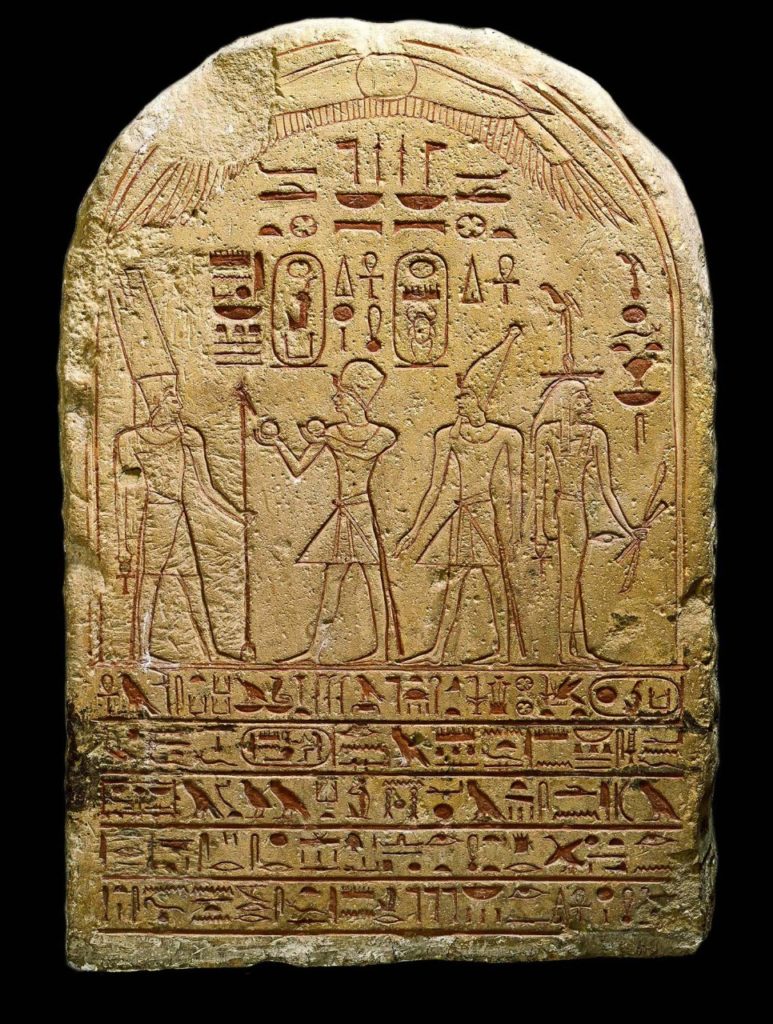

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut was known in antiquity as Djeser-Djeseru or the Holy of Holies. As with other grand Egyptian monuments, the purpose of the temple was to pay homage to the Gods and chronicle the glorious reign of its builder. The temple was commissioned in 1479 BCE and took around 15 years to complete. It was designed by Senenmut, a trusted adviser of Hatshepsut who was rumored to be her lover as well as the real power behind the throne.

The grand structure of the Mortuary Temple blends organically into the foothills of enormous limestone cliffs and the desert landscape of Upper Egypt. It marks the entrance to the Valley of the Kings and was also the site of the earlier mortuary temple and tomb of the founder of the 11th Dynasty (of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom), the great Theban prince Nebhepetre Mentuhotep (2040-1782 B.C.E.). The striking and almost modern façade of Hatshepsut’s temple is reminiscent of Greek or Roman architecture. What remains today beneath the cliffs of Deir El-Bahari is an effort of painstaking construction undertaken by the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw.

Though Senenmut closely modeled the building after the nearby mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II, Hatshepsut’s temple was built at a much grander and more elaborate scale and right next to the Mentuhotep’s.

The temple complex was laid out into three grand levels, each adorned with elaborate statuary, colonnades, and architectural reliefs. On the ground level is a large courtyard where, at one time, many exotic trees were planted from far-off lands. Reflecting pools and sphinxes lined the causeway to a ramp leading up to the second level. The second level houses the temple of Anubis, the God of the underworld – an indispensable feature of any mortuary temple. Also on the second level is the temple of Hathor, the goddess of fertility and women; an understandable dedication by a female pharaoh. The tomb of Senenmut is also on this level.

The third level features a portico with double rows of columns facing the front. It is also lined with statutes and several important structures, including the sacred sanctuary of Amun-ra, Royal Cult Chapel, and Solar Cult Chapel. Hatshepsut claimed divine lineage from the Sun god Amun, and he features prominently in these structures.

On either end of the third level is the Birth Colonnade where the story of Hatshepsut’s divine creation is carved in relief and the Punt Colonnade that conveys tales of her glorious and successful expedition to the mysterious Punt, the ‘Land of the Gods’ (believed to be modern-day Eritrea). Before Hatshepsut’s reign, Egyptians had not visited Punt in centuries (since the Early Dynastic period).

Although the depictions of Hatshepsut have a distinct air of femininity, she was frequently depicted in the ceremonial attire of a pharaoh with the traditional male headdress and false beard. She was also referred to with both male and female pronouns and titles, although the reality of her gender was apparent in text and was not intended to be disguised.

As Thutmose III grew older, he took control of the royal army and lead many successful overseas campaigns. He was an active expansionist and gained notoriety as a formidable warrior king. Over time, he reclaimed the throne of his father and his role as the sole king of Egypt. It is believed that Hatshepsut either died or was deposed in the 20th year of her reign around 1458 B.C.E. when she was between her mid-40s to early 50s.

Thutmose III succeeded to the royal throne and went on to rule for 30 more years after Hatshepsut. During his reign, Thutmose III eradicated almost all of the evidence of Hatshepsut’s rule. He demolished images of her as a king on temples and monuments and destroyed or replaced her name on cartouches with the names of Thutmose I, II, and III, thereby re-establishing the dynasty’s lineage of male succession. Historians knew little of Hatshepsut’s existence until 1822 when scholars started to decode hieroglyphics.

Since much of her history and the signs of her existence had been erased or written over, great mystery surrounded the cause of Hatshepsut’s death and the location of her tomb. Her mummy and final resting place remained a great mystery until it was finally discovered in 2007 in a site known as KV60 in the Valley of the Kings.

If you enjoyed the story of Hatshepsut, read about Nefertiti, another famous Egyptian woman.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!