Go into any art gallery the length and breadth of the UK and you are bound to find a Bomberg. David Bomberg, born in Birmingham in 1890 to Polish-Jewish immigrants, epitomises the term ‘artist’. Constantly developing his style and being seduced by the times and cultures he lived through, Bomberg’s works are a joy to behold.

In 1895, the family moved to Whitechapel, London and Bomberg was to become immersed in the culture of the East End of London which was reflected in his early works – the slum housing, public bath houses and the theatre were all subject matters against the backdrop of the First World War.

A student to Walter Sickert, the English painter and founding member of the Camden Town Group in the early part of the 20th Century, and a scholarship student of the Slade School of Fine Art, Bomberg was influenced early on by the Italian Futurists and their focus on the mechanised movement of the pictorial plane.

Connected to the Vorticist movement,the short-lived British avant-garde movement that began with Wyndham Lewis’s manifesto, ‘Blast’ committing artists to the industrial age who wished to ‘blast’ out of existence all that had been accepted before. The term ‘Vorticism’ came from the American poet, Ezra Pound, who said, “The Vortex is the point of maximum energy’ and works by Lewis, and artists such as Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, CRW Nevinson and Edward Wadsworth began to reflect that energy. The art critic, Frank Rutter stated that it was clear that these young artists “had constructed a new machinery for picture making”.

Although he did not sign the manifesto or claim to be a member of the group, Bomberg’s paintings were starting to cause a stir. Bomberg put forward a six painting contribution to the ‘Exhibition of Camden Town Group and Others’ in Brighton at the end of 1913, and was included as part of the ‘others’ section, Bomberg clearly did not wish to be aligned with one particular movement- he was not a ‘cubist’ nor was he really a Vorticist, but he carved out his own distinct style. In the catalogue for his own 1914 exhibition at the Chenil Gallery, he wrote: “…where I have used Naturalistic form, I have stripped it of all irrelevant matter… My object is the construction of Pure Form.”

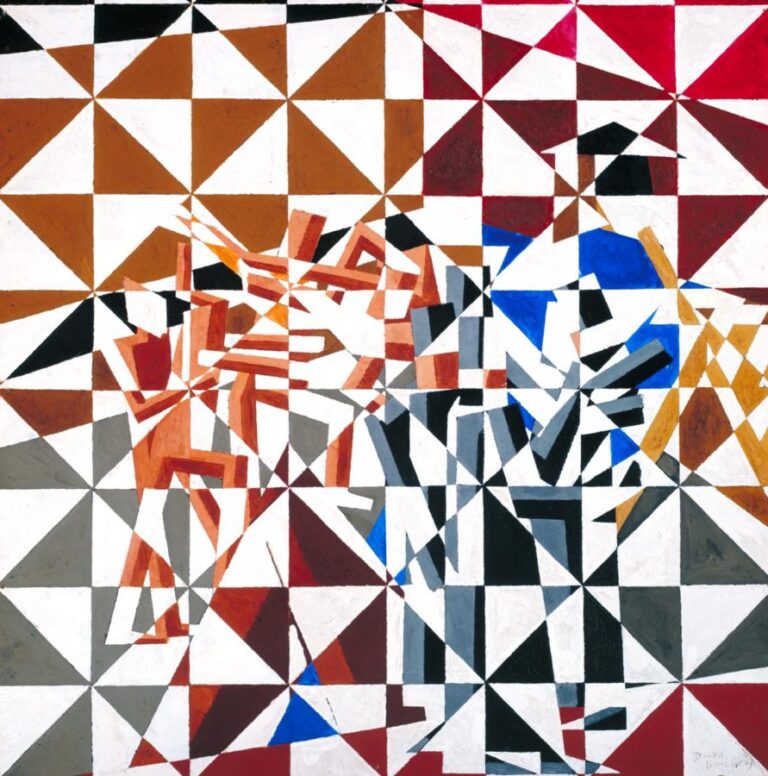

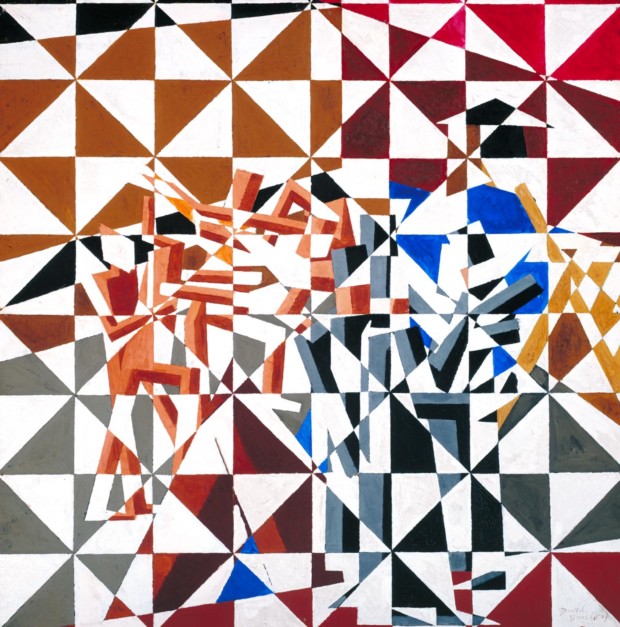

Ju-Jitsu of 1913 demonstrated this skill of removing all irrelevant matter. Dividing the canvas into 64 squares, Bomberg meticulously fragmented the fight into pure kinetic energy.

In 1914, Bomberg produced his most audacious, pure form work to date – The Mud Bath.

The East End public baths would have been visited by Bomberg as a young boy. Despite the angularity and the geometric positioning, there is a humanity about the figures that takes your breath away. Once you realise that the white and blue is light and shade, you start to see the forms in their different guises: the man diving in, the one on the bath’s edge, the head and arms of the man cutting through the water amongst them. This work caused much of a stir when it was hung outside the Chenil Gallery so it could be seen in the brilliant sunlight.

Bomberg enlisted in the First World War and the traumas that he experienced, deaths of friends and families left their mark on the sensitive young artist.

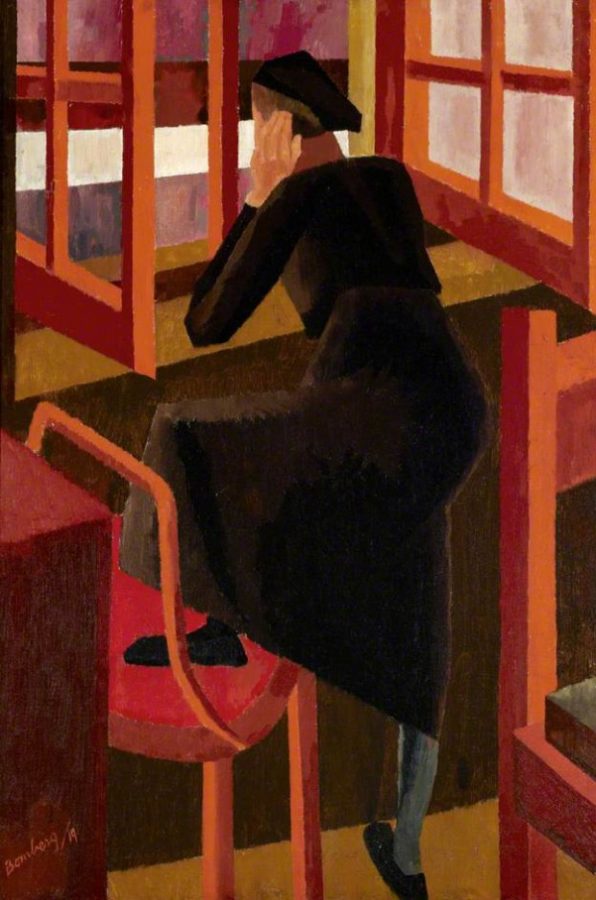

By the end of the war, Bomberg was still in a semi-vorticist phase as seen by the angles of the window, furniture and the central figure in At the Window (1919).

The red woodwork of the window cages to figure gazing out at an unseen vista. Painted in the middle of World War One, and with the woman in black, it could be interpreted as reflecting the futility of the war that was surrounding them.

Another interpretation could be a sense of being trapped within a claustrophobic domestic setting as the furniture behind and to the side is of the same red and her foot on the chair could signify her desire to escape through that window but she is powerless to make the leap. The perspective is slightly tilted so the creates an air of uncertainty – the question has to be asked: which way will she leap?

Post War Britain gave Bomberg a new outlet for his art. Bomberg returned to the place he knew well – the Jewish East End. Painted in 1920, this is a tightly composed work, entitled ‘Ghetto Theatre’ reflects Bomberg’s unease following his war experiences.

The two tiers show the divide between the well-to-do and the poorer element of society. The whole canvas is still, in comparison to his earlier works – the main figure leans towards the front of the painting, putting his full weight on his walking stick. The faces of the people above and below the gallery are mask-like in appearance, giving nothing away. The balcony forms a barrier, trapping the audience in their seats. The only element of vibrancy is the use of the red in the upper gallery and even then, it is bathed in shadow as the audience gaze impassively on the entertainment below.

Bomberg only used this style in the early part of his career. From the 1920s onwards, weary with what a post-war Britain now looked like and starting with a move to the countryside, Bomberg moved into a more representational style and away from his mechanised, angular forms to begin to explore, as he put it, “a personal communication with the land.”

Find out more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”0946590877″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/51HYgK2BfxIL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”120″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”8362737972″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/61L6KkPt1WL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”115″]