Book Review: Great Women Sculptors. Premiering in September!

There have been a plethora of recent surveys of women artists, including Phaidon’s own Great Women Artists (2019) and Great Women Painters...

Catriona Miller 23 September 2024

South Asia Institute, or SAI, located in the museum district in downtown Chicago on Michigan Avenue, cultivates the art and culture of South Asia and its diaspora through curated exhibitions, innovative programs, and educational initiatives. It was recently running an exhibition titled “Contemporary Chronicles” featuring contemporary artists from Pakistan and India.

Shireen and Afzal Ahmad are the founders of the South Asia Institute. Retired physicians, they have been collecting South Asian art for 50 years. They currently have over 900 works in their private collection. As collectors and founders of SAI, their vision is apparent in the current exhibit, “Contemporary Chronicles”. They are savvy collectors, well-versed in contemporary art practices and the international art scene. They are socio-politically aware and fully engaged with the complex geopolitical issues of our times. They also bring an insider/outsider perspective unique to the diasporic experience. Immigrants forever live in two worlds, the one they left behind and the one they live in now. They conduct a lifelong negotiation with the phenomenon of belonging. Not fully belonging to either world, but fully invested in both worlds.

Shireen Ahmad led the art tour of the exhibit and talked in-depth about each piece she had included in the “Contemporary Chronicles” exhibit.

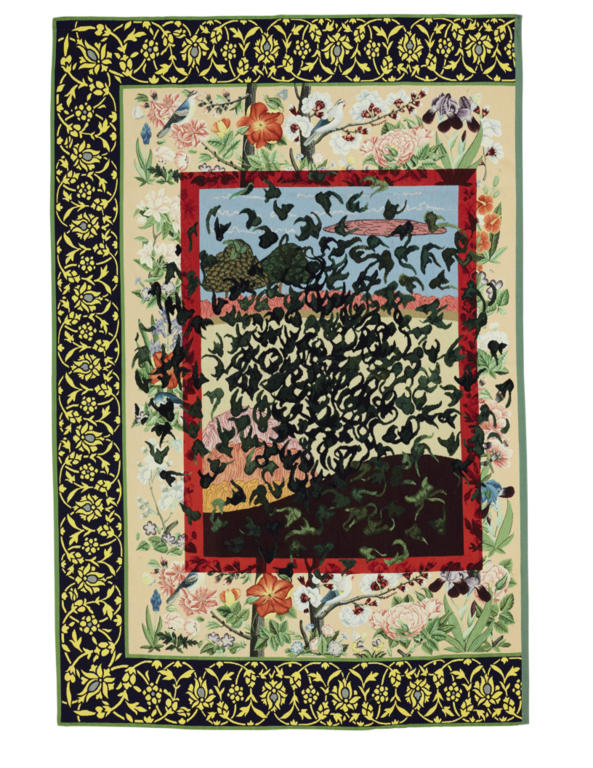

The first work was Shahzia Sikander‘s Pathology of Suspension, created in 2008. Scaled up from one of her miniature paintings, The Illustrated Page, it is the left-hand side of a page from an illustrated manuscript. Over 9′ tall (ca. 274 cm) and almost 6′ wide (ca. 183 cm), the work looms above the viewer.

“Contemporary Chronicles”: Shahzia Sikander, Pathology of Suspension, 2008, South Asia Institute, Chicago, IL, USA.

In addition to its size, the work features one of Sikander’s signature motifs – the Gopi’s hair, and in this work, it appears with a density and swirling energy. Sikander is known for inserting subversive political commentary in her beautiful works. Sikander has said:

The Gopis (female cow-herders in Hinduism, known for their devotion to the god Krishna) represent a feminine space, a multiplicity of female presence in a single frame. The Gopi-hair motif functions as a flock, reflecting the behavior of cellular forms that have reached self-organised criticality and resulting in a redistribution of both visual information and experiential memory.

Knowing this visual shorthand of the artist, images of the Afghani women protesting in the streets of Kabul flashed through my mind.

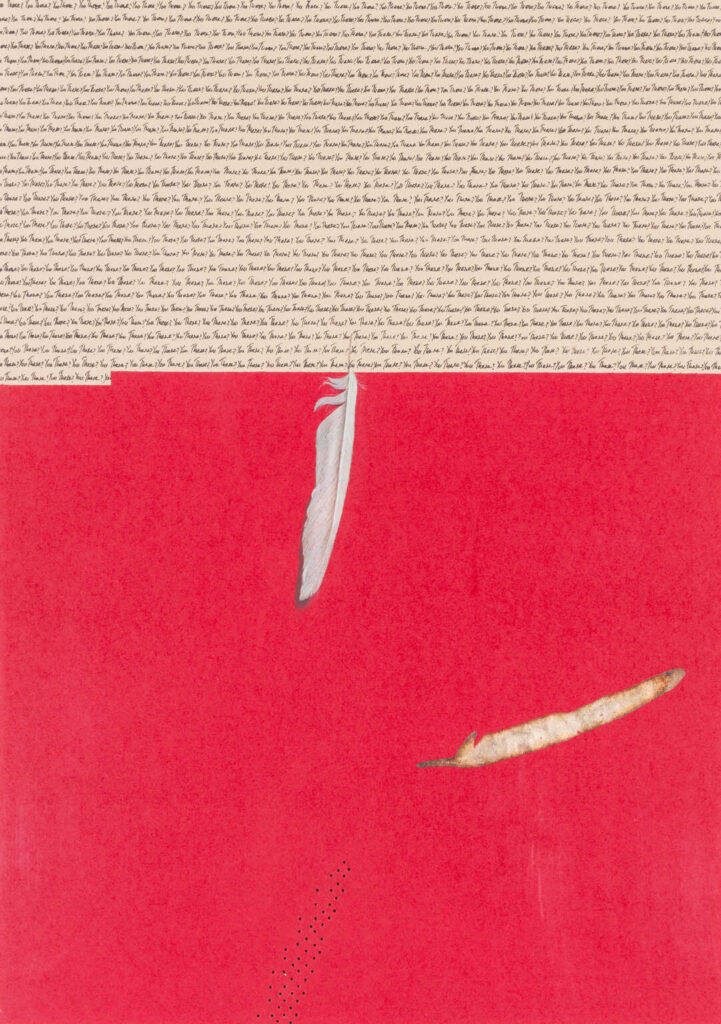

The subsequent was Abid Aslam’s Highly Noticeable, created in 2016. This work is a plaintive call for help to the divine.

“Contemporary Chronicles”: Abid Aslam, Highly Noticeable, 2016, South Asia Institute, Chicago, IL, USA.

The delicate calligraphy looks like Urdu script at first glance, but the words are written in English. The words say, “you there?” again and again. Below the text is a field of blood-red. As Shireen explained:

The feather floating down is a reference to a sign of hopefulness that a divine power might exist that will lead the nation towards the right path soon.

One is left wondering, which nation? America? Afghanistan? Pakistan? All of the above? 20 years came to pass since 9/11, and we don’t seem to have found the right path.

The following work was Tazeen Qayyum’s impactful work, Walking the True Path, made in 2015. Tazeen uses the motif of the cockroach in her work with beauty, humor, and savage political astuteness. Shireen mentioned that Tazeen started using the motif of the cockroach in her work in 2002, when the US launched the war on terror.

“Contemporary Chronicles”: Tazeen Qayyum, Walking the True Path, 2015, South Asia Institute, Chicago, IL, USA.

After the tour, Qayyum joined us via Zoom from her home studio in Canada. And she spoke at some length about how she came to use the humble cockroach in her work.

When I started using this motif, it was to depict the countless deaths and destruction caused by war and terror attacks. […] the value of human life is reduced to that of a pest insect, yet it also narrates the everyday human stories of resilience and triumphs over adversities.

She spoke about how the cockroach metaphorically stands in for immigrants in the post-9/11 environment of growing xenophobia, particularly Islamophobia in the West. Cockroaches as immigrants is a loaded metaphor.

In April 2015, Katie Hopkins, a columnist for The Sun newspaper, wrote:

Make no mistake, these migrants are like cockroaches.

The UN high commissioner for human rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, denounced her column, saying “cockroaches” was used by both the Nazis and those behind the genocide in Rwanda to describe the people they wanted to eliminate.

Qayyum has assembled a beautiful body of work using the cockroach motif. Visually stunning, it is a powerful commentary on xenophobia.

As we turned the corner into the next section of the museum, we were confronted with TV Santosh’s large oil painting on canvas titled A Survivor’s Testimony, created in 2009. Santosh works on the themes of war and global terrorism and paints in lurid greens and shocking orange, recreating the effect of a color photographic negative.

The artist fills his large canvases with figures contorted in pain. Santosh says in his artist statement that he lifts:

Pivotal episodes from recent history and renegotiates their appearance with a shock-bulb of violent energy that eclipses the work.

Shireen half-jokingly warns us that this next section of the exhibit has some challenging work. The Ahmads’ curatorial vision is admirable. They are not ones to shy away from complex, political artworks.

Zafar’s large hyper-realistic black and white drawings, created in 2015, exude a presence that is almost eerie. On jet black vinyl, Zafar engraves incredibly detailed images of children’s toys wrapped in gauze. Every thread and the frayed edge of the gauze has been rendered in exacting detail. One can almost physically feel the softness of the toy under the delicate gauze.

The toys are “wounded” and bandaged. It is a poignant juxtaposition of innocence and violence. It brings up images of innocent and terrified children in war zones and refugee camps.

Jitish Kallat has made a series of camo portraits of ordinary people in 2003, with the banner text Collateral Damage printed on them. The camo portraits could be alluding to military uniforms. Perhaps the artist uses camo as a visual shorthand to generalize the civilian victims of the war on terror and make them anonymous.

Collateral Damage represents civilian casualties of terrorist attacks and wars. The series had been made in 2003, shortly after the American war on terror began in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Wajahat Saeed’s red embroidered work, Am I Dead Yet? created in 2019, seems like a mass of red marks up close. Shireen asked us to look at Saeed’s painting from a distance. As the viewer steps back a few feet, three mutilated, dismembered bodies contorting in pain emerge from the sea of red.

With a storyteller’s flair, Shireen then told us that Saeed is a textile designer who has used embroidery to make artwork about the bomb blasts and drone bombings in his hometown of Parachinar, Pakistan. Located in the FATA area on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan, it has been subjected to at least 13 different bomb blasts in the last 20 years of the war on terror. He was forced to flee his home with hundreds of other families, and his work reflects the distress of the victims and survivors.

Shahid Rassam’s Untitled (Hota hai Shab-o-Roz) was created in 2016. It shows a mother and child wounded in a terrorist attack and their mouths are sewn shut. Newspaper clippings of news items about terrorist violence are collaged onto the drawings. This blend of words and images is a plea to curb worldwide terrorism. Rassam is also signaling that women and children suffer the severest consequences from acts of terrorism.

“Contemporary Chronicles”: Shahid Rassam, Untitled (Hota hai Shab-o-Roz), 2016, South Asia Institute, Chicago, IL, USA.

Shireen explained that Rassam’s title Untitled (Hota hai Shab-o-Roz) is based on a verse by the famous Urdu poet, Ghalib. It translates approximately to “The world is a children’s playground before me. Night and day, this theatre is enacted before me.”

The title implies that terrorism is now commonplace, an everyday occurrence.

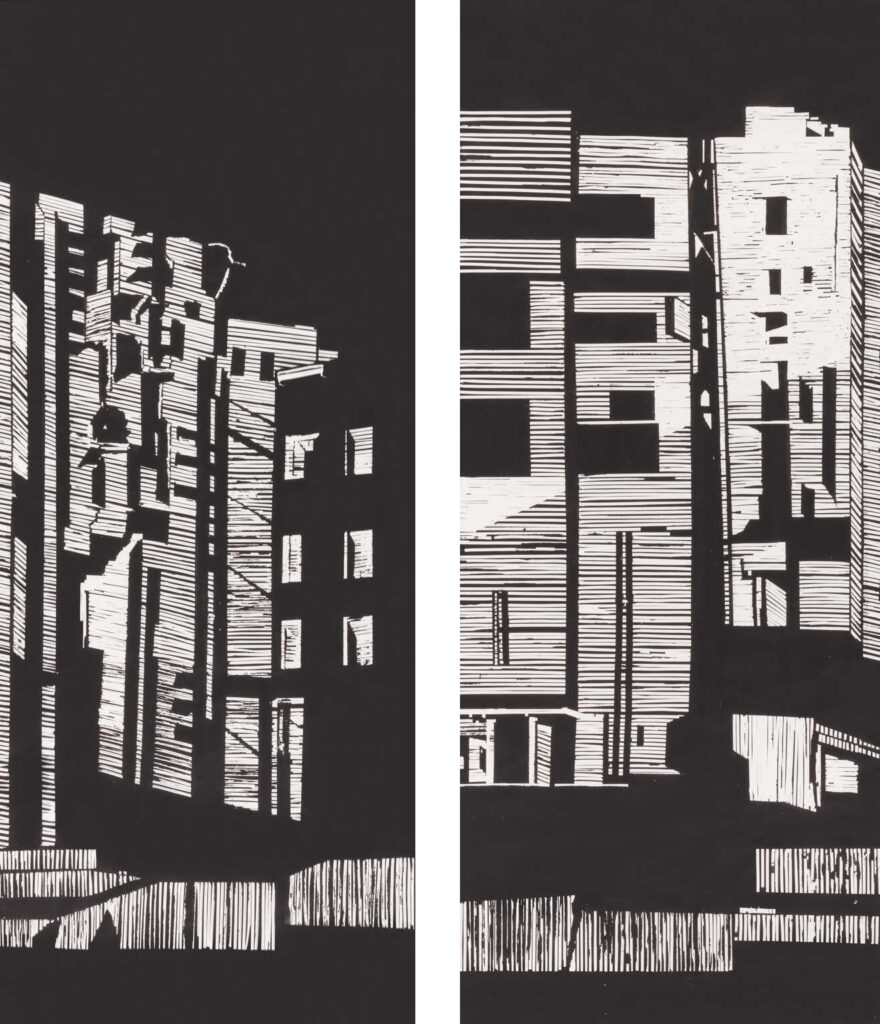

Next was Mina Arham’s two black and white, narrow and long paintings installed as a diptych. The black background has thick white lines that conjure up doors and windows of tall buildings. Shireen mentioned that the white lines are made from white-out tape, which is an unusual material to use.

Installed as a diptych, they look very much like the Twin Towers. Arham created these works in 2015 and they’re titled Geography of Somewhere. Arham is an artist and fresco-mural conservationist, and in this series, she is referring to older buildings that have been demolished.

“Contemporary Chronicles”: Mina Arham, Geography of Somewhere, 2015, South Asia Institute, Chicago, IL, USA.

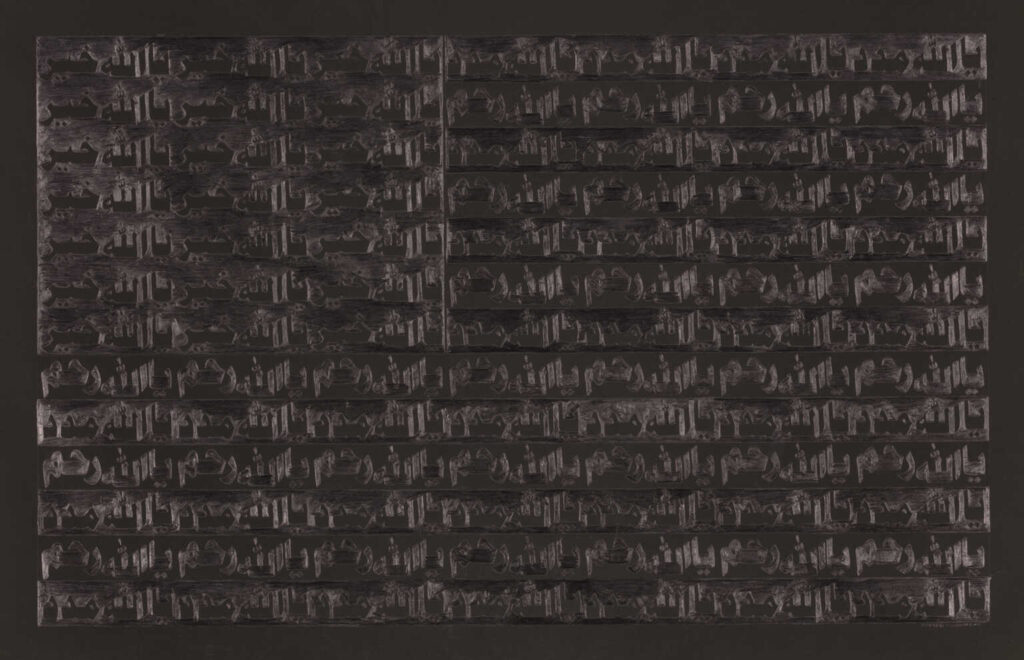

The last work in the show was this somber drawing by Muhammad Zeeshan, titled In God We Trust, made in 2015. This phrase is the United States’ official motto, and figures prominently in the American national anthem.

“Contemporary Chronicles”: Muhammad Zeeshan, In God We Trust, 2015, South Asia Institute, Chicago, IL, USA.

Zeeshan deconstructs the American flag, replacing the stars and stripes with Urdu script. He has used heavy layers of graphite on sandpaper to create this work. Shireen explained that Zeeshan explores global violence, social unrest, and political depravity in his art.

The dark grey graphite is mounted on a black background and framed in a dark graphite-colored frame. At almost 4′ x 5′ (122 x 152 cm), this is an imposing and somber work.

The world as we knew it in 2001 has changed dramatically in the last 20 years. And it is no coincidence that all the artworks in this show were made after 2001. Even though the show was not overtly about 9/11, the effects of the war on terror were the main focus of the exhibit (right?), internalized in the psyches of everyday people, especially in South Asia and the Middle East.

Author’s Bio:

Pritika Chowdhry is an artist, curator, and writer. Her works are in public and private collections. She has shown her works in the Weismann Museum in Minneapolis, Queens Museum in New York, the Hunterdon Museum in New Jersey, the Islip Art Museum in Long Island, and other prestigious venues. Pritika has an MFA in Studio Art and an MA in Visual Culture and Gender Studies from UW-Madison. More info about Pritika can be found at her website.

A. Dawood: Shahzia Sikander in Conversation with Anita Dawood, OCULA, 18 Mar 2016.

S. Jones. UN human rights chief denounces Sun over Katie Hopkins ‘cockroach’ column, The Guardian, 24 Apr 2015.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!