Summary

Read our review of African Art Now, a guide to contemporary African Art featuring profiles of 50 artists on the rise. The review is complemented by an interview with Osei Bonsu, the book’s author, curator, and writer.

African Art Now

In recent years, African art has gained increasing popularity, not just among eager collectors and lovers, but on a much broader scale. Exhibitions across museums and galleries, as well as auctions and new art fairs, have all contributed to the rise of interest in the most recent expressions of African art, and a whole new generation of artists is gaining international recognition and appreciation.

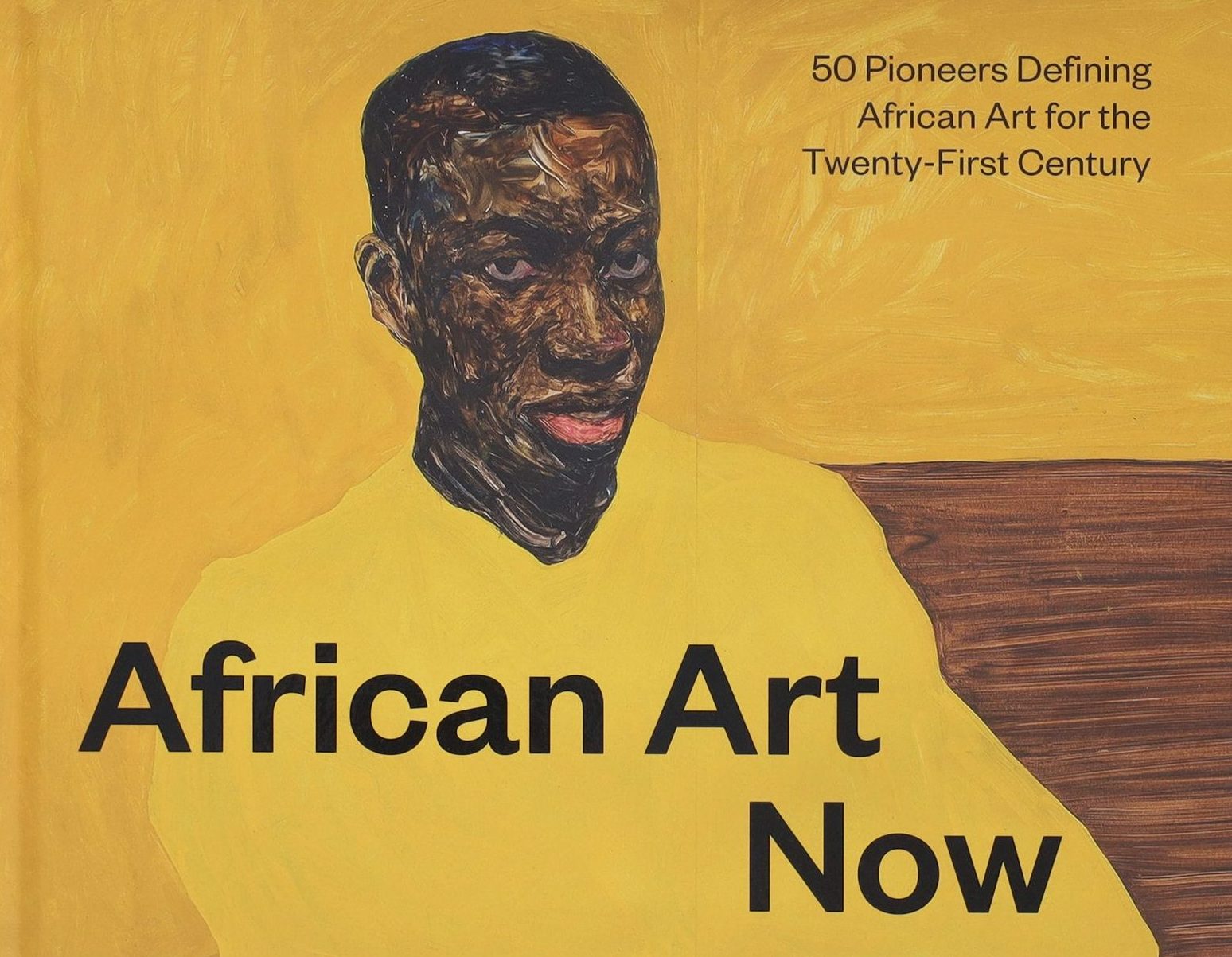

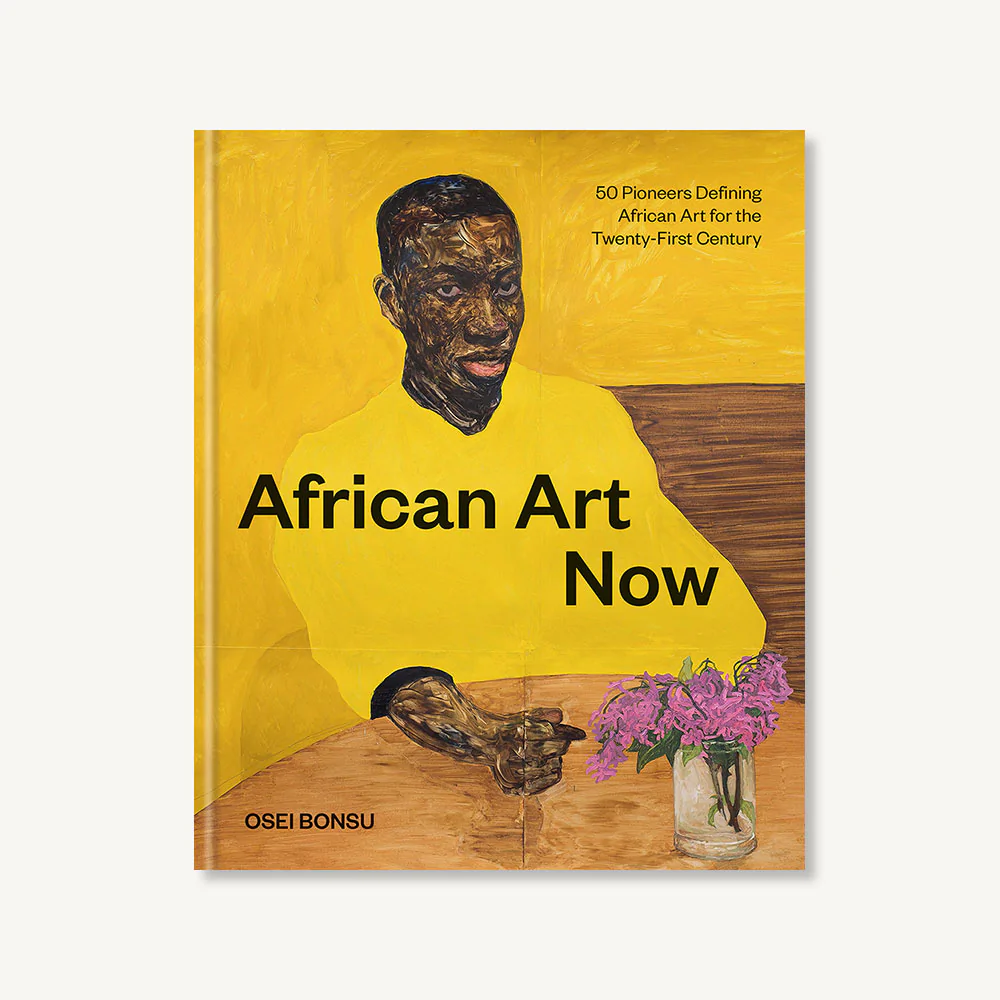

Book cover of African Art Now: 50 Pioneers Defining African Art for the Twenty-First Century by Osei Bonsu, published by Chronicle Books 2022. Courtesy of the publisher.

African Art Now, the latest publication by Osei Bonsu, investigates the work of 50 rising artists, redefining African art in the 21st century. The artists that Bonsu chose to represent are both African and African-diasporic, giving a much wider and more interesting perspective on the state of African art today.

Kudzanai Chiurai, Revelations VIII, 2011, in African Art Now: 50 Pioneers Defining African Art for the Twenty-First Century by Osei Bonsu, published by Chronicle Books, 2022. Courtesy of the publisher.

The book is aesthetically superb, but its real value lies in the meticulous work that the author did to research and compile the profiles of each featured artist. Bonsu introduces each one, giving us information about their background, work, and most prominent themes behind their work, enriching and illustrating each essay with full-color reproductions of their works.

Featuring artists coming from all over Africa, as well as African diasporic ones, the book is able to investigate a whole new generation of artists. As Bonsu states in the book introduction:

Rather than a standard historical survey, African Art Now uncovers artists who emerged in the decade between 2010 and 2020, a period of widespread critical and commercial change in the field of contemporary African art.

African Art Now: 50 Pioneers Defining African Art for the Twenty-First Century.

Despite the broad and hugely diverse backgrounds and careers of the featured artists and the vast array of different mediums they work with, Bonsu was able to trace five major social, political, and historical themes that help contextualize the works and approach of each artist. From identity, family portraits, and traditions to postcolonial and environmental issues, the book offers a comprehensive insight into different practices and approaches, reflecting on Africa both as an idea and an experience.

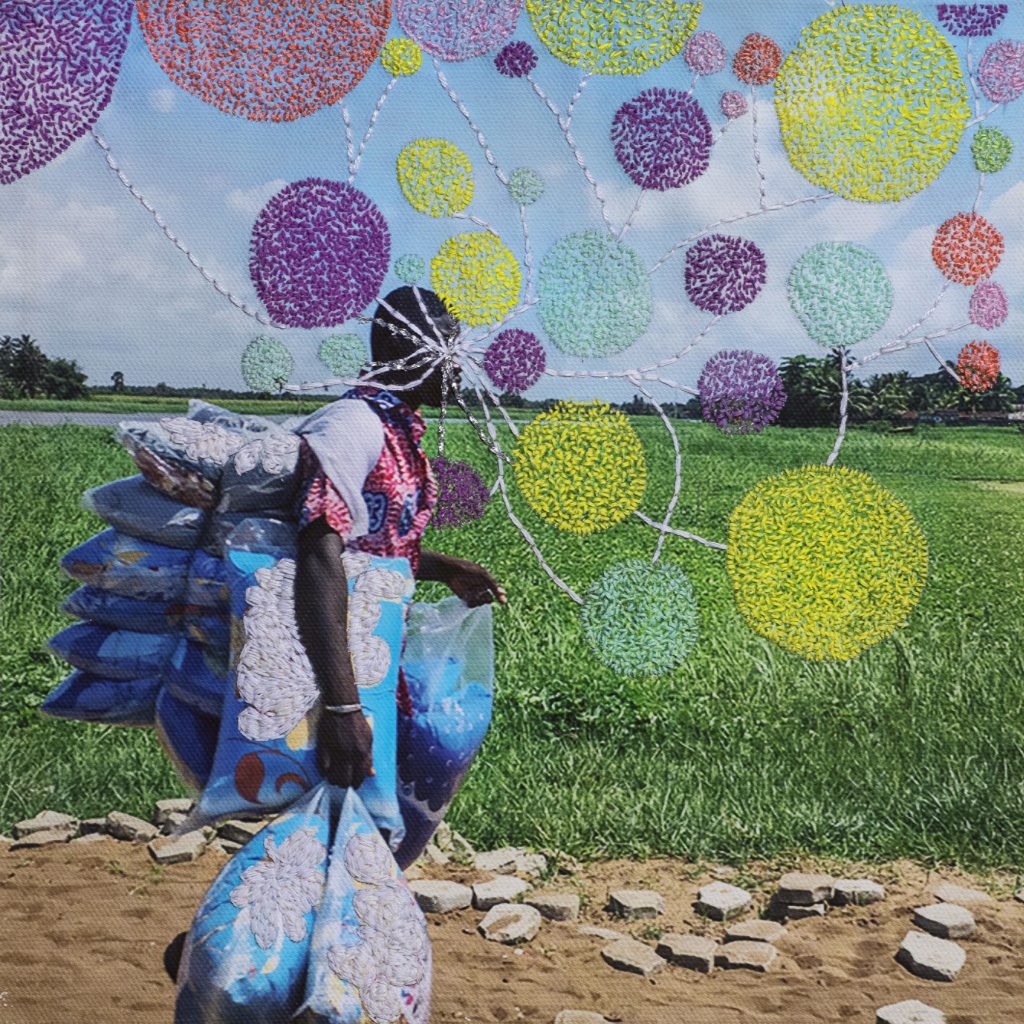

Joana Choumali, Sans titre, 2019, from the series Ça va Aller, in African Art Now: 50 Pioneers Defining African Art for the Twenty-First Century by Osei Bonsu, published by Chronicle Books, 2022. Courtesy of the publisher.

Joana Choumali, Sans titre, 2018, from the series Ça va Aller, in African Art Now: 50 Pioneers Defining African Art for the Twenty-First Century by Osei Bonsu, published by Chronicle Books, 2022. Courtesy of the publisher.

Osei Bonsu

Osei Bonsu is a British-Ghanaian curator and writer based in London and Paris. In 2020, Bonsu was named one of Apollo magazine’s “40 under 40” leading African voices. He is a curator of international art at Tate Modern in London, UK. We talked to Osei Bonsu to get a deeper perspective on his work and fully understand the project behind the publication.

Carlotta Mazzoli: African Art has had significant growth in popularity over the last decade, both in terms of the number of exhibitions and market. How does your book position itself in this discourse? Is it meant for the general public, as a first approach to African art for people who are not entirely familiar with the subject? Or is it more like a photograph of what African art is nowadays?

Osei Bonsu: There has been a significant growth of interest in contemporary African art over the last decade. When I began working in the field of contemporary African art as a curator and writer about 10 years ago, there was some skepticism about the very idea that African art could, in fact, be truly contemporary. There was still a fixation on the classical tradition of African sculpture as being more “authentically” African art, and some artists had chosen to align themselves with the international art scene for fear that their work would be considered too “African” by the global mainstream. The book takes as a point of departure the transformative field of contemporary African art as an important development in the art world. It is dedicated to the artists who are helping to shape the diverse landscape of African art with a sense of pride and purpose—a rootedness in the beautiful paradox of being African in a globalized and cross-cultural society. The book is intended for a general audience who wants to understand how these artists have been shaped by social, political, and cultural narratives. It is also filled with incredible works—I would like to see people engage with the material on multiple levels.

Edson Chagas, Emmanuel C. Bofala, Patrice J. Ndong, 2014, from the series Tipo Passe, in African Art Now: 50 Pioneers Defining African Art for the Twenty-First Century by Osei Bonsu, published by Chronicle Books, 2022. Courtesy of the publisher.

CM: Talking about social, political, and cultural narratives, in the book you pinpoint five major themes that inform and link different artists, namely Shifting Identities, Reclaiming History, Postcolonial Dystopias, The Family Portrait, and Future Ecologies. Why do you think these themes are so relevant for people coming from hugely diverse backgrounds, geographical areas, and socio-economic environments? Are those themes universal, in your opinion?

OB: For me, the themes were a way of anchoring the artists in a framework that helps to expand possible readings of their work. In relationship to the very idea of pan-African identity, many of the artists were born in the 1980s, when the immediate euphoria of independence had worn off. Some of them were economic migrants. Some grew up in upper-middle-class African or African diaspora households. Some were trained in international art academies. Some came to art as a second or third career. What connected these artists was their commitment to particular social and cultural narratives that may seem universal but are, in fact, deeply rooted in African art. Narratives around the restitution of cultural artifacts, the challenges of climate emergency, and the idea of the family as an expanded community of chosen relations are all central to the book. I’d like to think that we can think of African issues as being central to global narratives.

CM: Talking about the artists, how did you select them? Which criteria guided you in the selection? And how could you distill the broad and vastly heterogeneous subject of African contemporary art into this relatively small selection of artists?

OB: Selecting 50 artists from such a rich and diverse field was a challenge. The question I kept coming back to was: Will these works matter in 20 years? There have been several African art books dedicated to African artists who began their careers during the second half of the 20th century. Many of those books had a strong emphasis on the condition of postcolonial theory as the dominant mode of artistic research and expression for good reason. I’m not sure whether this is true of most of the African art produced today. As the book outlines, artists today are thinking about an expansive range of ideas and approaches to artmaking that blend multiple histories and cultural traditions that engage critically with the postcolonial, decolonial, and even pre-colonial frameworks. The challenge was to bring together 50 artists whose works will likely influence 50 more artists who may not yet have been born. To do this, it was important to think about artists as belonging to an interconnected network. Oftentimes, one can see the parallel lines of influence converge in surprising and meaningful ways.

Em’Kal Eyongakpa, Untitled XI (Ketoya), Ketoya speaks/(Dɛnyaland- Kɛnyaŋland-Kɛyakaland; a century later), 2016, in African Art Now: 50 Pioneers Defining African Art for the Twenty-First Century by Osei Bonsu, published by Chronicle Books, 2022. Courtesy of the publisher.

Em’Kal Eyongakpa, Untitled 8, 2011, from the series Naked Routes. in African Art Now: 50 Pioneers Defining African Art for the Twenty-First Century by Osei Bonsu, published by Chronicle Books, 2022. Courtesy of the publisher.

CM: On that note, the artists you chose to represent in the book are all fairly young, but you already indicated them as pioneers of 21st-century African art. Do you think these artists will have a long-lasting impact on African art and where it is likely to go in the upcoming years? Or do you foresee different practices and themes emerging in the near future?

OB: The book looks specifically at practices that developed within the last 10 years. Oftentimes, there was little written about their works due to their relative lack of visibility or exposure. As a curator, I take seriously the role we play as champions, mentors, and critical friends of artists; it is the ultimate privilege of the work we do. By shining a spotlight on a younger generation, my aim was to draw upon the relationships I have nurtured and the artists who have shaped my experience of art. As we look ahead to the future, it’s important we prioritize intergenerational conversations around the value of arts and culture in society. The book looks at artists who are shaping important and challenging conversations that will hopefully connect with a diverse community of readers and art lovers. I believe their practices will continue to expand and develop well into the 21st century.

CM: Lastly, talking about the future, in which directions do you wish Western institutions (and African ones, too) will be developing in the upcoming years, specifically in regard to African art? What are the fields that still need to be improved, and what can we actively and collectively do to promote those changes?

OB: At the back of the book, there is an index of African art institutions shaping change on the continent. One of the most important developments we have seen in recent years is artists setting up museums and cultural institutions on the continent. Whether it’s diaspora artists who retain close connections to their countries of origin or artists who have chosen to remain rooted in their local communities, this shift could have a lasting impact on the field of African art. What African Art Now aims to do is open up 50 practices that shape the landscape of African art—but this work doesn’t exist in a vacuum. None of the art in the book would exist without the dedication and teamwork of the countless artists, educators, and curators who sustain local and international art ecosystems. I hope the book encourages people who see the breadth and complexity of African art in all its glory.

You can get your own copy of African Art Now on the publisher’s website!