Camille Claudel in 5 Sculptures

Camille Claudel was an outstanding 19th-century sculptress, a pupil and assistant to Auguste Rodin, and an artist suffering from mental problems. She...

Valeria Kumekina 24 July 2024

1 July 2024 min Read

Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013) is the most globally recognized Inuit artist. Pioneering the way, she was among the first Inuit artists to garner national and international acclaim. Her lifetime achievements include prestigious honors such as the Companion of the Order of Canada, the Order of Nunavut, and the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts.

Notably, her masterpiece, Owl’s Bouquet, has adorned the Canadian ten-dollar bill since 2017. In tribute to her legacy, the Kenojuak Cultural Centre and Print Shop was established alongside the Kenojuak Ashevak Memorial Award; both dedicated to fostering contemporary Inuit artists.

Ashevak’s artistic expression is characterized by vibrant colors and unique amalgamations of floral, animalistic, and human elements, encapsulating profound beauty.

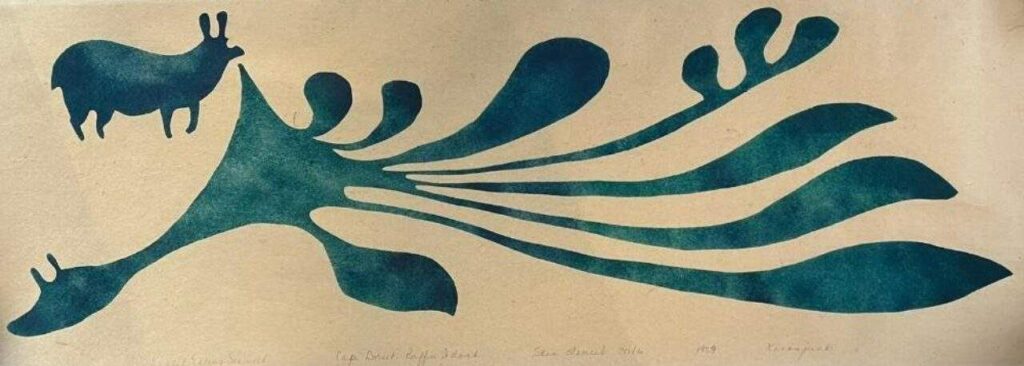

Kenojuak Ashevak, Rabbit Eating Seaweed, 1959, skin stencil, Kinngait, Canada.

In her early life, Kenojuak Ashevak was still part of the traditionally nomadic Inuit lifestyle before she settled down in Kinngait (previously known as Cape Dorset), Canada. As part of this traditional lifestyle, she developed her artistic skills through various traditional crafts such as embroidery. She started engaging in more acknowledged artistic activities in her early twenties when she began carving.

James and Alma Houston, local government workers, discovered Kenojuak Ashevak’s talent and encouraged her to redirect her work into a new medium and redefine it as part of the graphic arts movement from the 1960s onwards. The main artistic mediums of Kenojuak Ashevak were drawing, acrylic painting, sculpting, and, most famously, stone-cut prints.

Kenojuak Ashevak, The Arrival Of The Sun, 1962, Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, Canada. Artsy.

Sculpting and stone-cut prints were generally the two most common art forms of the Inuit culture that were recognized as art instead of craft during this period. This type of printing was still closely connected to sculpting during this period as the prints were produced by intricately carving the desired form into a stone surface, applying the ink to the stone, and stamping the ink-dipped sculpted form on paper or cloth.

In this context, it is significant to note that the printing process was frequently executed by different individuals who specialized in making the print itself as clean as possible. This maintained the desired colors and their transitions. Kenojuak Ashevak, for example, regularly worked with various printmakers, such as Eegyvudluk Pootoogook or Qavavau Manumie. This guaranteed the vibrancy of the distinctive colors of Kenojuak Ashevak’s art.

As time passed, printing techniques diversified, and Kenojuak Ashevak gained access to linoleum-based printing and a greater diversity of colors and textures to use in her prints.

Rabbit Eating Seaweed is the first print by Kenojuak Ashevak, which had previously been designed as an embroidery pattern for a seal’s hide. The presence of seaweed implies a connection to water, which is further enhanced by the uneven division of navy blue ink imitating the flow of water.

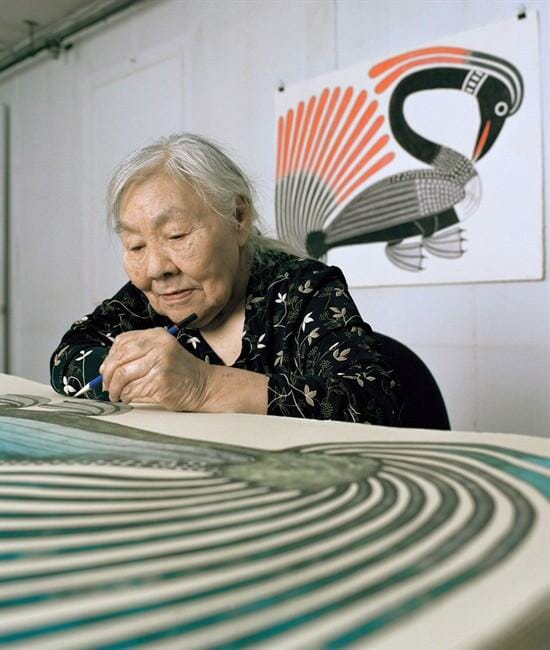

Photograph of Kenojuak Ashevak at work. Fishink.

Six-Part Harmony is one of the stone-cut creations by Kenojuak Ashevak, printed by Qavavau Manumie. Manumie described Six-Part Harmony as one of the most challenging prints to execute due to its fine lines and clear divisions between the vibrant colors that truly make the characters come to life.

Kenojuak Ashevak, Six-Part Harmony, 2011, stone-cut print, Dorset Fine Arts, Kinngait, Canada.

The owl is one of the most recurring characters in Kenojuak Ashevak’s art. She even famously said:

There is no word for art. We say it is to transfer something from the real to the unreal. I am an owl, and I am a happy owl. I like to make people happy and everything happy. I am the light of happiness and I am a dancing owl.

IAQ, “Kenojuak Ashevak Breaks Records at Auction,” Inuit Art Quarterly 31, no. 4 (2018).

One of the recurring interpretations for the frequent recurrence of owls in Kenojuak Ashevak’s art is the significance of snowy owls in Inuit shamanism and living experiences. Snowy owls are, next to the raven, the only bird that overwinters in the arctic regions.

Furthermore, snowy owls frequently appear close to Inuit settlements to scavenge for leftovers. Hence, they are recurrently featured in Inuit visual culture and mythology in various contexts due to their continuous proximity to Inuit experiences. Two of the snowy owl’s multifaceted associations in Inuit mythology are transformation and light.

This is especially relevant to Kenojuak Ashevak’s artistic inspirations. For instance, she described the shapes of the shadow figures she created with her hands on the snow as one of her primary sources of inspiration for her art. Cecile Pelaudeix interpreted these shadow figures as being closely connected to both the direct reflection of the absence and presence of light and the continuous flux or transformation due to the potential movements of her hand.

Pelaudeix has argued that this inspiration formed a natural extension of the Inuit cultural associations with the ever-present snowy owls. This led Kenojuak Ashevak to express herself creatively by featuring snowy owls predominantly.

It is essential to highlight this central inspiration of Kenojuak Ashevak, showing the profound beauty of nature rather than necessarily connecting all her art back to cultural references. She, for instance, states in an interview that the principal objective of her artistic process is to “make something beautiful, that is all.”1

Kenojuak Ashevak, Happy Little Owl, 1969, stone-cut print, Kinngait, Canada.

Happy Little Owl is believed to be Kenojuak Ashevak’s only possible self-portrait. This speculation is primarily based on the title she used to describe herself as “a happy owl.”

While the owl remained one of the most featured characters in Kenojuak Ashevak’s art, it is notable that her art underwent significant changes throughout her career. Pelaudeix even distinguished four distinctively different phases within Kenojuak Ashevak’s art.

As Pelaudeix defines it, the first phase is a primary natural element, such as feathers, rays of light, or leaves, that encircles a secondary human or animalistic character.

In the second phase, many of her artworks feature a single feminine face representing Sedna, the Inuit central deity of animals and the ocean. According to Pelaudeix, this phase generally portrays many references to Inuit mythology, such as the featuring of Sedna and various animals central to that mythology, including the raven and the snowy owl.

The third phase is more abstract and is defined through the novel inclusion of a diversity of abstract geometric forms within her art.

The fourth phase circles back to the representation of the human form.

Yet, this fourth phase integrates the diversification of multiple human genders, forms, faces, and dynamics. In this connection, it is relevant to note that Kenojuak Ashevak exclusively represented a feminine perspective in her art as she stated: “I make art that represents women because I am a woman.”2

This applies to the masculine elements within her later art, which, according to Pelaudeix, represent not necessarily men but rather the high complexities of gender and specifically the masculine aspects of female characters.

Two Spirits, for instance, represents the perfect combination of masculine and feminine elements. The feminine aspects are defined by featuring the ulu, the traditional knife of Inuit women, while the masculine elements are defined by one of the traditional hunting knives of Inuit men.

Both creatures feature the feminine ulu in the beak of the lower creature and the hands of the upper creature. Yet, the upper creature incorporates two masculine hunting knives as legs and represents the intricate balance between feminine and masculine aspects within one creature.

Kenojuak Ashevak, Two Spirits, 1967, stone-cut print, Kinngait, Canada.

Lastly, it is essential to acknowledge that Kenojuak Ashevak was a central figure in the decolonial representation and visibility of both the Inuit population in general as well as the negotiations and cultural legitimization for the independence of Nunavut on the first of April 1999. The featuring of her art on the Canadian ten dollar bill and various Canadian postage stamps is a direct acknowledgment and celebration of the political establishment of Nunavut.

As one of the most central Inuit artists, Kenojuak Ashevak significantly and positively influenced Inuit art and how art was perceived within that community.

This expanded outside the Inuit community into international recognition and shaped how Inuit culture and art were perceived internationally. In her role as Inuit artistic ambassador, Kenojuak Ashevak primarily focused on constructive, creative expression by supporting young artists and maintaining her art’s unique character.

She mentored her sons, Adamie and Arnaqu Ashevak, and her nephew, Tim Pitsiulak, who became one of the most influential contemporary Inuit artists. Consequently, Kenojuak Ashevak has a long-lasting constructive and joyful remembrance both within the Inuit communities and beyond, inspiring generations of artists until today.

Kenojuak Ashevak, The Enchanted Owl, 1960, stone-cut print, Kinngait, Canada.

This is one of the Canadian stamps featuring Kenojuak Ashevak’s work in celebration of the establishment of Nunavut in 1999. This one features The Enchanted Owl, which Kenojuak Ashevak described as one of her favorites.

Cecile Pelaudeix, Art Inuit: Formes de l’Âme et Représentations de l’Être: Histoire de l’art et anthropologie, Grenoble: Éditions de Pise, 2007, p. 16.

Pelaudeix, Art Inuit, p. 142.

Britt Gallpen, John Geoghegan, Taqralik Partridge, Evan Pavka and Alysa Procida, “How has Printmaking Evolved at Kinngait Studios in the Last Sixty Years?” Inuit Art Quarterly 32, no. 3 (2019).

Cecile Pelaudeix, Art Inuit: Formes de l’Âme et Représentations de l’Être: Histoire de l’art et anthropologie, Grenoble: Éditions de Pise, 2007.

Darlene Coward Wight, “Kenojuak Ashevak,” Canada’s National History Society 96, no. 1 (2016), p. 28.

IAQ, “Kenojuak Ashevak Breaks Records at Auction,” Inuit Art Quarterly 31, no. 4 (2018).

IAQ, “Kenojuak Cultural Centre Opens Its Doors in Kinngait,” Inuit Art Quarterly 31, (2018).

IAQ, “30 Ways To Describe An Owl According to Kenojuak Ashevak,” Inuit Art Quarterly 32, (2020).

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!