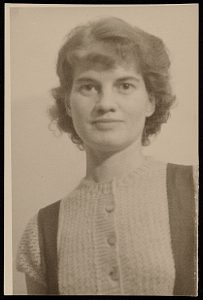

It’s hard to imagine that a female artist could be advised to leave her work unsigned to avoid prejudicing the gallery owner, but for women artists in the 1920s, this was not an unusual problem. For Elsie Driggs (1898-1992), this battle would continue throughout most of her career.

Born in Connecticut, but brought up in New York and Philadelphia, Driggs brought to her canvases a sense of “livingness”, whether it was from her works of plants and flowers, landscapes and animals or of the industrial subjects she became best known for. She once said “I want chemistry- something happening.”

One of her most famous works is Pittsburgh, from 1927, a painting that has often been linked to the American Precisionists; artists who brought out the beauty of the newly emerging industrial landscape with clean lines, simplified form and an influence from structure and form of the renaissance. Driggs denied that this work was inspired by the artists of the movement, but that her influence was from the 15th century artist, Piero della Francesca.

Driggs had lived in Pennsylvania and vowed to return to paint the steel plants that had dominated her landscape. The canvas is dominated by the four smokestacks rising through the wispy clouds billowing at the base of the painting. The guidelines are delicately crisscross between them. The pipes and tanks below contrast with the rigidity of the stacks. The subtlety of the palette used adds to the ethereal, hazy quality of this work.

When discussing her works based on the steel mills and factories that she grew up with, Driggs said, “You looked directly …into these big forms, and I kept finding them beautiful and wondering why. I told myself I wasn’t supposed to find a factory beautiful, but I did.”

Thankfully, Driggs refused to submit her work anonymously for the exhibition of 1928 by the Daniel Gallery in New York, which included works by the male Precisionists. One critic singled out Driggs surmounting the male artists in the show: “Done in sooty blacks and velvety greys, she has woven her factory chimney into a beautiful pattern, truthful, yet imaginative.”

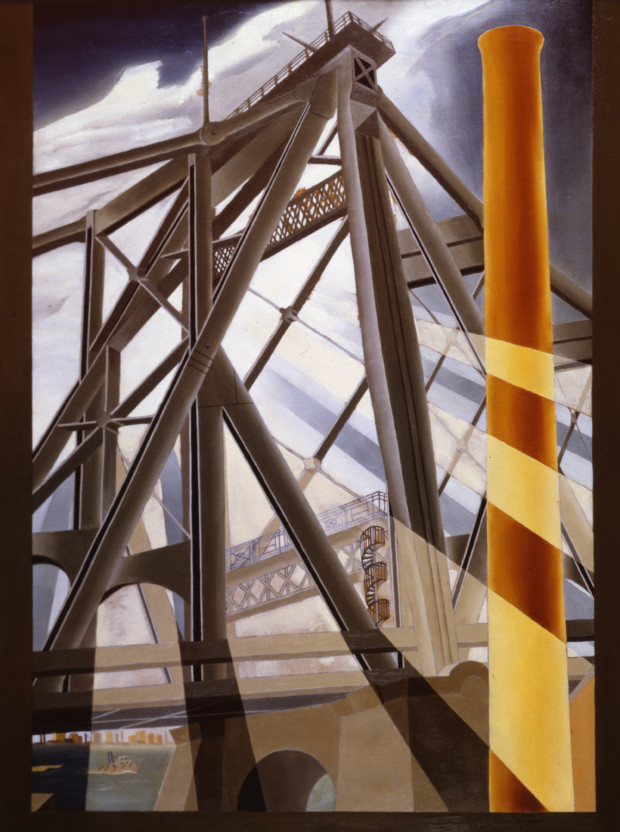

Driggs produced relatively few paintings of this style with Queensborough Bridge (1927) being another example.

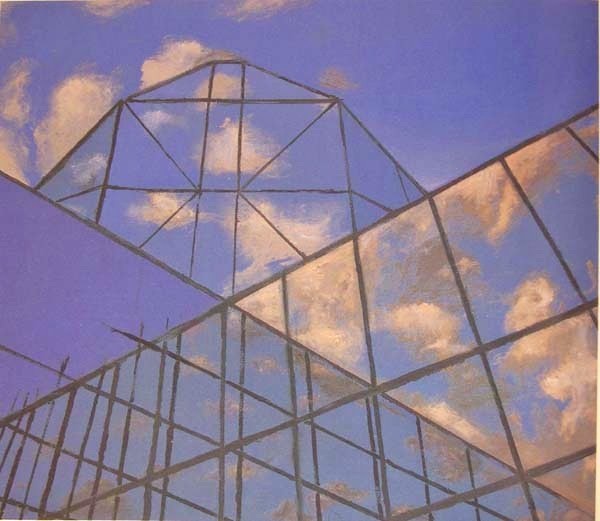

However, it is clear that Drigges produced works that held to her conviction that beauty could be found in unexpected places:

Further reading:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”0812241045″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/41L8gFaediL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”110″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”B002M057DQ” locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/41zVBFupSL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”120″]