‘Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera’ is an ongoing exhibition from the Metropolitan Museum of Art that opened on December 17, 2018. The exhibition is on the second floor, in the Lila Acheson Wallace Wing, occupying galleries 917-925.

Many of the artists are familiar staples of abstract art. Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Cy Twombly and Robert Motherwell are all represented in the collection. The paintings are large, with either a thin frame surrounding each canvas or no frame at all. The challenge for the Metropolitan Museum was to present the familiar subject of abstract art in a new and exciting way. I think the Met succeeded in doing this.

A quote from Barnett Newman sets the tone:

“We felt the moral crisis of a world in shambles, a world devastated by a great depression and a fierce world war, and it was impossible at that time to paint the kind of painting that we were doing—flowers, reclining nudes, and people playing the cello…So we actually began…as if painting were not only dead but had never existed.”

The Met then goes on to refute Newman’s premise, that an art movement can exist and thrive independently of what preceded it. I don’t think this is possible, but who knows? The artwork that follows provides the answer.

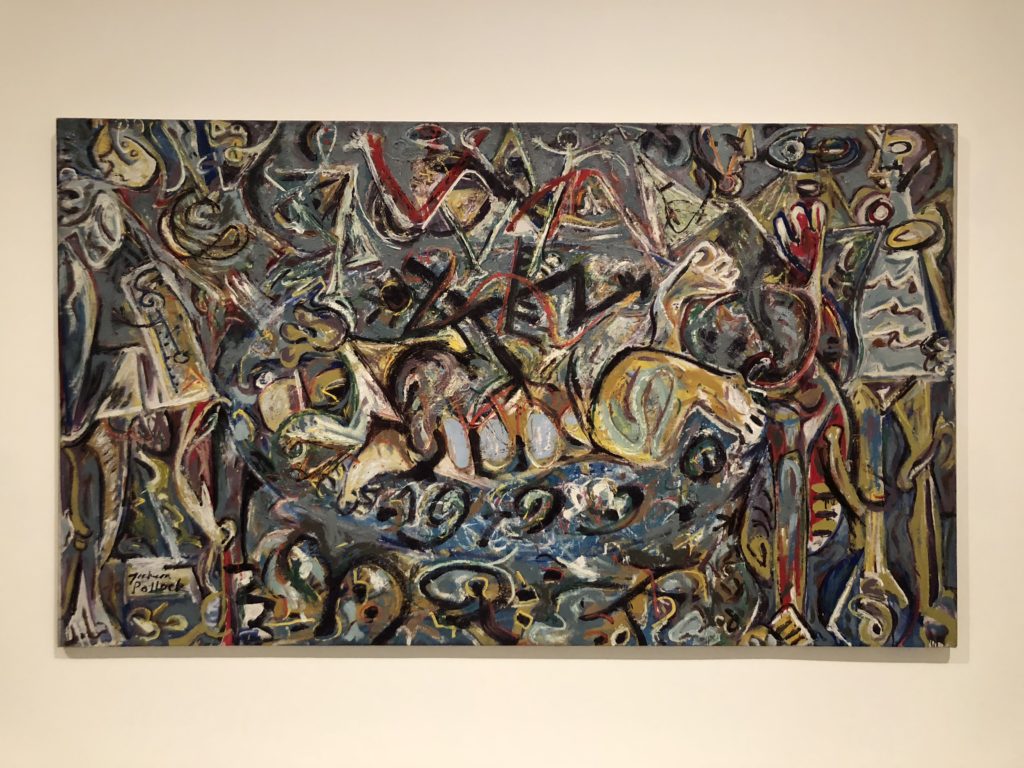

In one of the first rooms of the exhibition is the Jackson Pollock painting Pasiphaë, from 1943. This abstract-appearing painting has many figurative elements, most noticeably a standing figure on the right edge of the canvas. All the elements of the design are pressed against the picture plane, forcing the viewer to become more aware of the surface and texture of the canvas. The Met’s description of this painting includes the following thought: “The painter developed this novel interpretation of the Surrealist technique of automatism (which taps the artist’s unconscious to compose the image) by creating dozens of colored drawings…”

I am not tempted to search through the painting, hoping to identify other figures and other representations of reality. Reality fades away when one lets it go, and what one is left with is an exciting, vibrant explosion of shapes and colors that dazzle the imagination. The painting provides a foreshadowing of what was to come—the Jackson Pollock drip paintings—and this painting more than holds its own on its own merits. I take in the composition of this canvas all at once. My eye does not travel from a central point of interest to other parts of the painting. My gaze is not guided anywhere. Instead, the whole painting is seen at once. And when I get close to the painting, about two feet away, the small portion of the painting that I see at that moment is behaving the same way as its full-sized image. Each smaller piece stands on its own merits, a painting within a painting, endowed with the same attributes as the complete painting taken in as a whole.

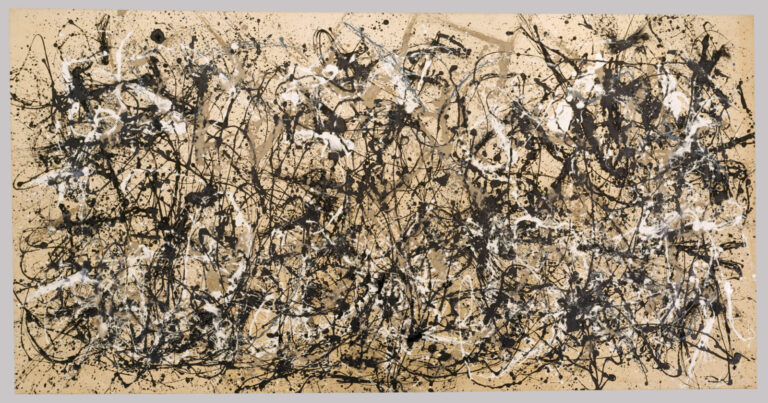

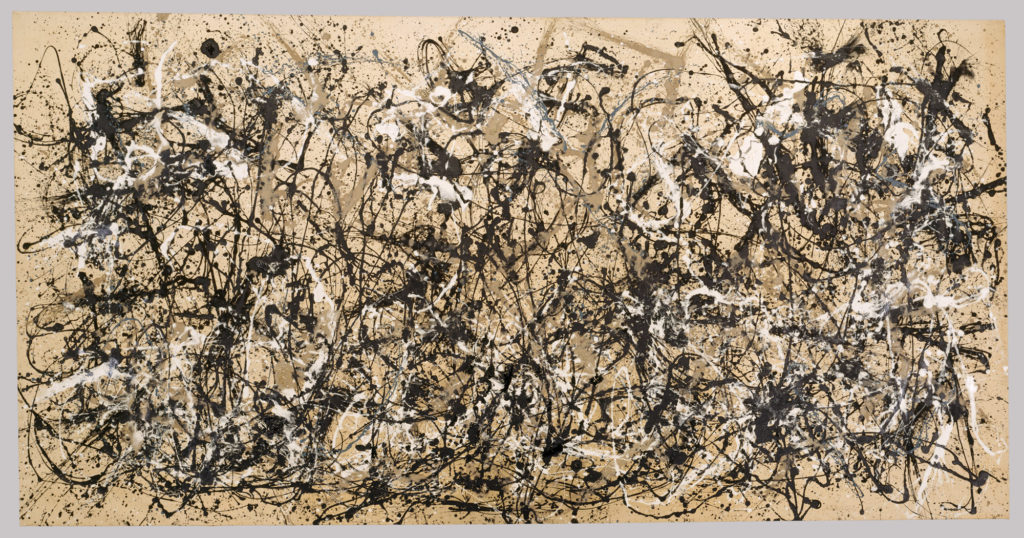

In the same room is a much bigger Pollock painting, Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), from 1950. This painting had been acquired by the museum “in 1957, a year following the artist’s unexpected death—a sign of how quickly his reinvention of painting was accepted into the canon of modern art.”

Also in the same room are several pages from a Jackson Pollock sketchbook. Several drawings done in colored pencil are shown as well. These colored pencil drawings are absolutely beautiful. After being mesmerized by these drawings for the better part of a half an hour, I was able to see their influence clearly in Autumn Rhythm (Number 30). When Pollock is pouring enamel paint onto his canvas, he is not doing so blindly. He is doing so from the perspective of a trained artist whose stylistic preferences had been honed for many years. That is the lesson of these drawings, drawings so beautiful that they would be equally wonderful if Pollock had never made a single brushstroke or dripped a single drop of paint. The most figurative of the colored pencil drawings is Untitled from 1938-1941. A nude woman is lying on her back in the foreground, faceless, with two other nude women above her, emerging from a Georgia O’Keefe-like curtain of female genitalia. The other drawings are more abstract, and all of them are beautifully composed.

The connection between the Pollock drawings and the Pollock paintings is one of the reasons why this exhibition is special.

Color field paintings by Mark Rothko are also included in this exhibition. As with Pollock, the Met includes examples of paintings that Rothko did before he settled into his signature style. There are two untitled watercolor paintings from 1944-1946 that provide an interesting introduction to the paintings that follow, all of which are deeply moving. The brightest painting with the most contrast is No. 13 (White, Red on Yellow) from 1958.

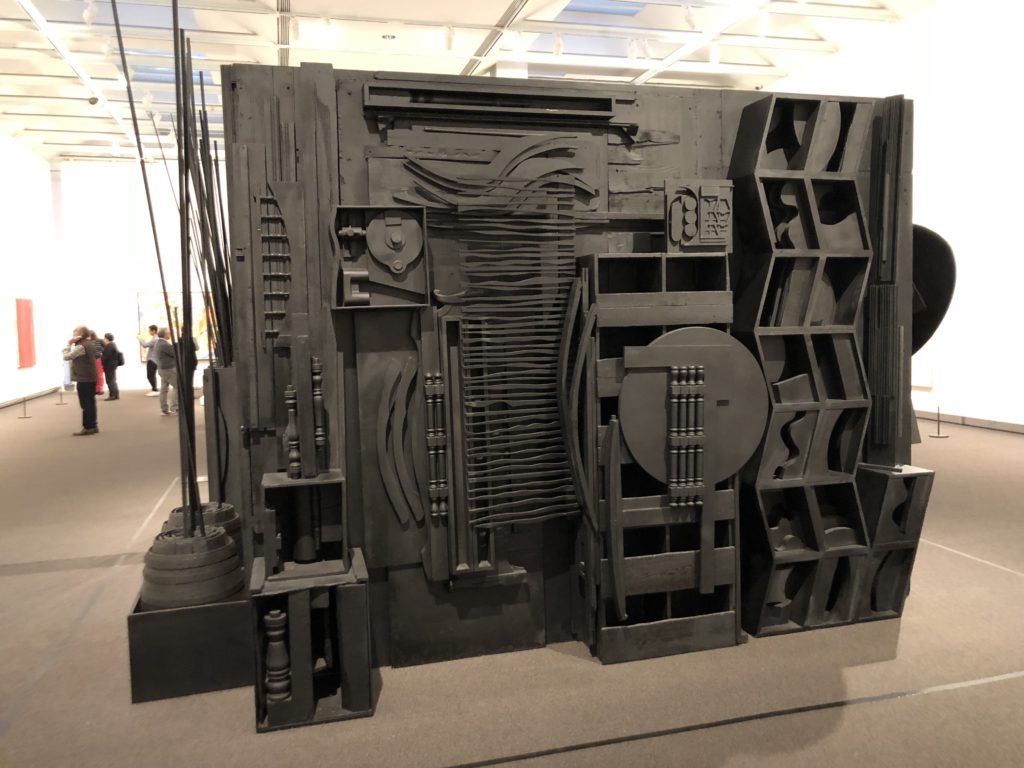

Louise Nevelson’s Mrs. N’s Palace, from 1964-77, made out of painted wood and mirror, is one of the highlights of the exhibition. What beautiful shapes! This one-room wooden home of geometric forms that coexist beautifully together has an inviting entrance, and were it not for the nearby sign prohibiting anyone from walking through the open entrance, I would have been thrilled to walk inside and live in there for a while.

Examples of op art include October, by Kenneth Noland, from 1961. Carmen Herrera’s Equilibrio, from 2012, is a much more appealing painting with three black isosceles triangles that are also six white right triangles. The negative and positive areas of the composition are equal.

A more recent piece in the exhibition is Elizabeth Murray’s Terrifying Terrain, from 1989-1990. The piece is described as oil on shaped canvases. The Metropolitan Museum writes that this painting “conjures the precariousness of an awe-inspiring rock climbing trip to Montana.’ Elizabeth Murray used to teach at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. I knew her from SVA many years ago, I was in one of her classes, and I wish I had had the openness of mind at that time to pick her brain and learn from her on her terms. She was passionate about art, especially abstract art, and had a wealth of information to impart. I feel fortunate that I am able to enjoy her work now, as part of this wonderful ongoing exhibition.

Learn more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”3836529076″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/61TNpFUl9WL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”90″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”145215659X” locale=”UK” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/41AL6CNODbL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dail005-21″ width=”83″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”0870704931″ locale=”UK” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/51G1DKTS8RL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dail005-21″ width=”98″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”0300160259″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/51uCSch2oHL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”95″]