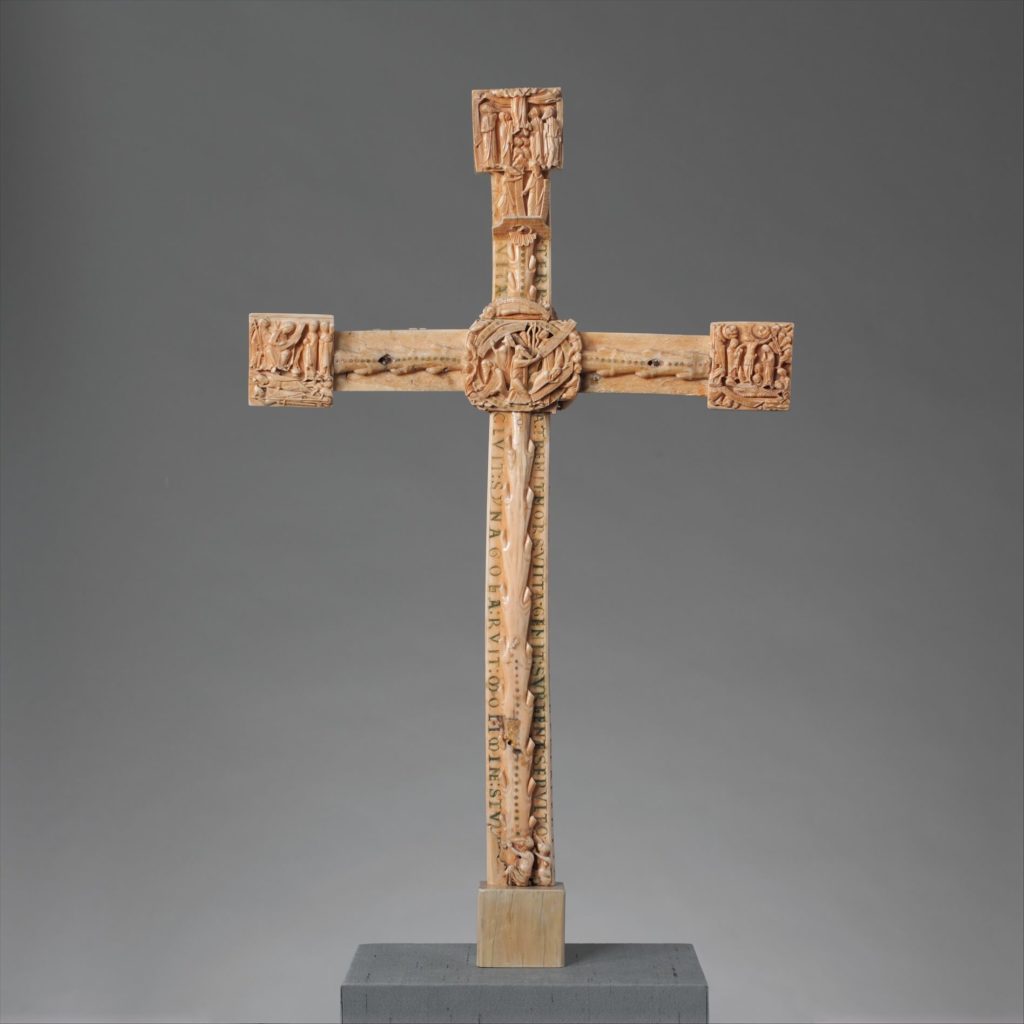

The Cloisters Cross is a beautiful English Romanesque walrus ivory cross, likely dating to the middle of the 12th century. From the moment it reappeared in the mid-20th century, art historians have considered it to be one of the great treasures of the Middle Ages.

Both sides of the cross contain scores of little carved figures and inscriptions – almost a hundred of each. The scenes include events from the Old and New Testaments, including episodes from the Crucifixion and Resurrection, the Lamb of God, various prophets, and symbols of the Evangelists.

Not all that much is definitively known about the cross. Experts agree that it is English. Its exact date and place of production are still a matter of debate, though it was probably for a monastery. And we’re unlikely to ever know for sure the identity of its maker. It doesn’t help than the cross’s former owner continuously refused to tell anyone how or where he got the cross – information that could have substantially aided research.

There isn’t anything else quite like it in the world. Other ivory crosses exist, as do large crosses made out of metal or wood, but none of them really compare to the Cloisters Cross. Nothing else is as detailed and full of complex theology. Since it has no close parallels among medieval ivories, scholars have looked more often to illuminated manuscripts for stylistic comparisons. The cross would have been carried in processions and may have also been displayed on an altar.

In the front (top-most image), the shaft of the cross is carved to look like branches of a tree. This is a reference to the Tree of Life, and it’s fitting for a crucifix. The Christian tradition sees the crucifixion of Christ as the beginning of eternal life for the faithful, so connections are often drawn between the wood of the cross and the Tree of Life. A figure of the crucified Christ (called a corpus) would have once appeared on this side of the cross. However, it is now lost. Near the bottom, tiny figures of Adam and Eve cling to the cross/tree, since the Crucifixion redeems them of their sins. On the back (below), the shaft and arms contain a series of tiny prophets holding scrolls. On both sides, medallions in the center and square plaques on each of the ends contain Biblical scenes and symbols of the Evangelists. The plaque that would have been at the base of the cross is now lost.

In addition to the profuse figural carvings, the cross also contains lots of inscriptions. Two are written in larger letters up and down the shaft – one is on the front on either side of the Tree of Life, and the other is along the sides. The rest are on little scrolls held by the carved figures. They’re so small that the phrases on them are heavily abbreviated. The ideas behind the phrases and images chosen is an example of typology – a theological concept in which events from the Old Testament are paired with similar events from the New Testament, which they are thought to prefigure. For example, the central medallion on the front of the cross references the Brazen Serpent. This was an Old Testament event in which God instructed Moses to make a bronze snake and mount it on a wooden stick in order to cure plague-stricken Israelites. Christian typology saw the raising of the snake as a parallel to Christ being raised up on the cross, since both caused people to be saved. You can see the Brazen Serpent image in center of this photo, along with scenes from of the Deposition, Resurrection, and Ascension of Christ in the three square terminals. In the photo below that, you can see the Lamb of God in the center, with Evangelists’ symbols on the terminals and prophets on the crossbar.

Both of the large inscriptions and several of the smaller ones have a decidedly anti-Jewish attitude, painting Jews as enemies of Christ. For example, the inscription on the sides of the cross shaft reads (translated from the Latin); “Cham laughs when he sees the naked private parts of his parent. The Jews laughed at the pain of the dying God.” It’s known that there was some pretty strong anti-Jewish sentiment in England at this time, and such diatribes showed up a fair bit in early and medieval Christian thought. Some scholars believe that the anti-Jewish aspects of the Cloisters Cross came from a place of outright hatred on the part of its owner or maker, while others think that the inscriptions were instead intended to convert local Jews. More recently, scholars Elizabeth Parker and Charles Little have suggested that the anti-Jewish aspects of the inscriptions have previously been misinterpreted and might actually refer to the tradition of Christian-Jewish theological debate. It’s difficult to know what to make of it, but this is definitely a dark aspect of an otherwise beautiful cross.

The Cloisters Cross only got that name recently in its history. It refers to The Cloisters, the Metropolitan Museum of Art‘s medieval collection in Upper Manhattan, which has owned the cross since 1963. The story of how this came to be is pretty spectacular. In 1960, when the cross was owned by a mysterious European collector, it came to the attention of a young Cloisters curator named Thomas Hoving. Hoving, who was later the Met’s director, became fascinated with the cross and worked tirelessly for three years to acquire it for the Cloisters. It was an extended adventure that involved lots of drama and tricky negotiations. Many top museums in the United States and Britain wanted the cross, so Hoving had to fight long and hard to purchase it for the Met. Hoving wrote a book about the event, called King of the Confessors. It’s a wonderful read, which I highly recommend.

The Cloisters Cross is one of the Cloisters’ most famous and important works. Two of the others are the Unicorn Tapestries and the Merode Altarpiece, and you can read about both right here on DailyArt Magazine.

Sources:

Hoving, Thomas. King of the Confessors. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981.

Parker, Elizabeth C. and Charles T. Little. The Cloisters Cross: Its Art and Meaning. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994. Accessed online.

Learn more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”0671433881″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/51QniCL3cyL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”73″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”1872501907″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/31pO3tsQYL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”84″]